Background

At work we practice continuous integration in terms of performance testing alongside different stages of functional testing.

In order to do this, we have a performance environment that fully replicates the hardware and software used in our production environments. This is necessary in order to be able to find the limits of our system in terms of throughput and latency, and means that we make sure that the environments are identical, right down to the network cables.

Since we like to be ahead of the curve, we are constantly trying to push the boundaries of our system to find out where it will fall over, and the nature of the failure mode.

This involves running production-like load against the system at a much higher rate than we have ever seen in production. We currently aim to be able to handle a constant throughput of 2-5 times the maximum peak throughput ever observed in production. We believe that this will give us enough headroom to handle future capacity requirements.

Our Performance & Capacity team has a constant background task of:

- increase load applied to the system until it breaks

- find and fix the bottleneck

Using this process, we aim to ensure that we are able to handle spikes in demand, and increases in user numbers, while still achieving a consistent and low latency-profile.

There is actually a third step to this process, which is something like ‘buy new hardware’ or ‘modify the system to do less work’, since there is only so much than tuning will buy you.

Identifying a bottleneck

During the latest iteration of the break/fix cycle, we identified one particular service as problematic. The service in question is one of those responsible for consuming the output of our matching engine, which can peak at 250,000 messages per second at our current performance-test load.

When we have a bottleneck in one of our services, it usually follows a familiar pattern of back-pressure from the application processing thread, resulting in packets being dropped by the networking card.

In this case however, we could see from our monitoring that we were not suffering from any processing back-pressure, so it was necessary to delve a little deeper into the network packet receive path in order to understand the problem.

Understanding the data flow

Components involved in network packet receipt

The Linux kernel provides a number of counters that can give an indication of any problems in the network stack. Since we are concerned with throughput, we will be most interested in things like queue depths and drop counts.

Before looking at the available statistics, let’s take a look at how a packet is handled once it is pulled off the wire.

The journey begins in the network driver code; this is vendor-specific

and in the majority of cases open source. In this example, we’re working

with an Intel 10Gb card, which uses the ixgbe driver. You can find out

the driver used by a network interface by using ethtool:

ethtool -i <device-name>

This will generate output that looks something like:

driver: ixgbe

version: 3.19.1-k

firmware-version: 0x546d0001

bus-info: 0000:41:00.0

supports-statistics: yes

supports-test: yes

supports-eeprom-access: yes

supports-register-dump: yes

supports-priv-flags: no

The driver code can be found in the Linux kernel source here.

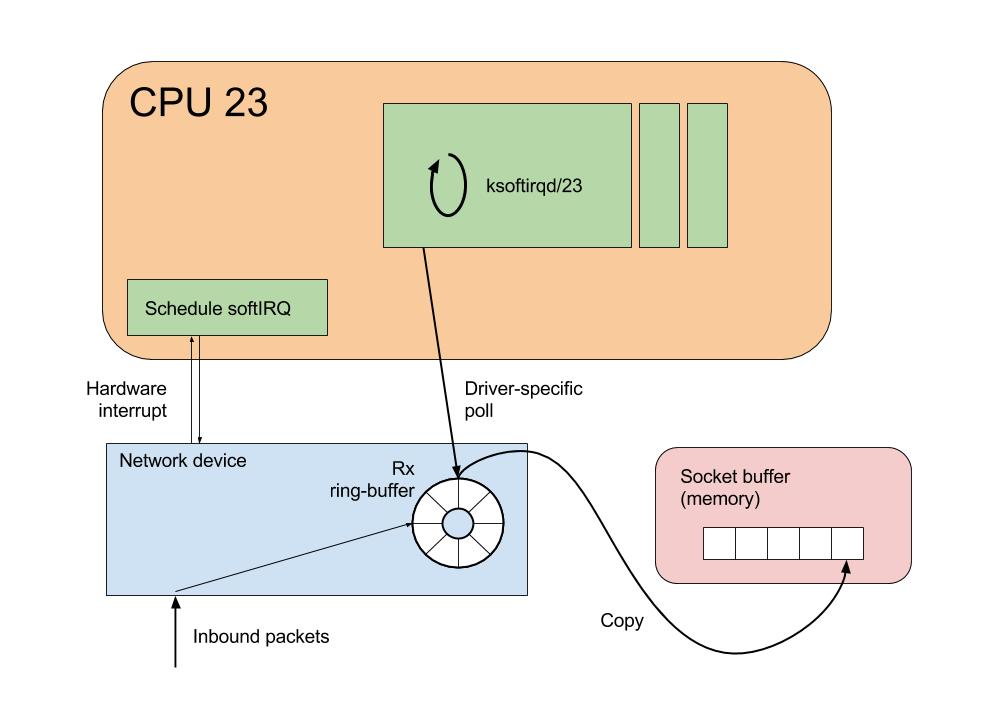

NAPI

NAPI, or New API is a mechanism introduced into the kernel several years ago. More background can be read here, but in summary, NAPI increases network receive performance by changing packet receipt from interrupt-driven to polling-mode.

Previous to the introduction of NAPI, network cards would typically fire a hardware interrupt for each received packet. Since an interrupt on a CPU will always cause suspension of the executing software, a high interrupt rate can interfere with software performance. NAPI addresses this by exposing a poll method to the kernel, which is periodically executed (actually via an interrupt). While the poll method is executing, receive interrupts for the network device are disabled. The effect of this is that the kernel can drain potentially multiple packets from the network device receive buffer, thus increasing throughput at the same time as reducing the interrupt overhead.

Interrupt handling

When the network device driver is initially configured, it first associates a handler function with the receive interrupt. This function will be invoked whenever the CPU receives a hardware interrupt from the network card.

For the card that we’re looking at, this happens in a method called ixgbe_request_msix_irqs:

request_irq(entry->vector, &ixgbe_msix_clean_rings, 0,

q_vector->name, q_vector);

So when an interrupt is received by the CPU, the ixgbe_msix_clean_rings method simply schedules a NAPI poll, and returns IRQ_HANDLED:

static irqreturn_t ixgbe_msix_clean_rings(int irq, void *data)

{

struct ixgbe_q_vector *q_vector = data;

...

if (q_vector->rx.ring || q_vector->tx.ring)

napi_schedule(&q_vector->napi);

return IRQ_HANDLED;

}

Scheduling the NAPI poll entails adding some

work

to the per-cpu poll list maintained in the softnet_data structure:

static inline void ____napi_schedule(struct softnet_data *sd,

struct napi_struct *napi)

{

list_add_tail(&napi->poll_list, &sd->poll_list);

__raise_softirq_irqoff(NET_RX_SOFTIRQ);

}

and then raising a softirq event. Once the softirq event has been

raised, the driver knows that the poll function will be called in the

near future.

softirq processing

For more background on interrupt handling, the Linux Device

Drivers book has a chapter dedicated to

this topic. Suffice to say, doing work inside of a hardware interrupt

context is generally avoided within the kernel; while handling a

hardware interrupt a CPU is not executing user or kernel software

threads, and no other hardware interrupts can be handled until the

current routine is complete. One mechanism for dealing with this is to

use softirqs.

Each CPU in the system has a bound process called

ksoftirqd/<cpu_number>, which is responsible for processing softirq

events.

In this manner, when a hardware interrupt is received, the driver raises

a softIRQ to be processed on the ksoftirqd process. So it is this

process that will be responsible for calling the driver’s poll

method.

The softirq handler

net_rx_action

is configured for network packet receive events during device

initialisation. All softirq events of type NET_RX_SOFTIRQ will be

handled by the net_rx_action function.

So, having followed the code this far, we can say that when a network

packet is in the device’s receive ring-buffer, the net_rx_action

function will be the top-level entry point for packet processing.

net_rx_action

At this point, it is instructive to look at a function trace of the

ksoftirqd process. This trace was generated using

ftrace,

and gives a high-level overview of the functions involved in processing

the available packets on the network device.

net_rx_action() {

ixgbe_poll() {

ixgbe_clean_tx_irq();

ixgbe_clean_rx_irq() {

ixgbe_fetch_rx_buffer() {

... // allocate buffer for packet

} // returns the buffer containing packet data

... // housekeeping

napi_gro_receive() {

// generic receive offload

dev_gro_receive() {

inet_gro_receive() {

udp4_gro_receive() {

udp_gro_receive();

}

}

}

netif_receive_skb_internal() {

__netif_receive_skb() {

__netif_receive_skb_core() {

...

ip_rcv() {

...

ip_rcv_finish() {

...

ip_local_deliver() {

ip_local_deliver_finish() {

raw_local_deliver();

udp_rcv() {

__udp4_lib_rcv() {

__udp4_lib_mcast_deliver() {

...

// clone skb & deliver

flush_stack() {

udp_queue_rcv_skb() {

... // data preparation

// deliver UDP packet

// check if buffer is full

__udp_queue_rcv_skb() {

// deliver to socket queue

// check for delivery error

sock_queue_rcv_skb() {

...

_raw_spin_lock_irqsave();

// enqueue packet to socket buffer list

_raw_spin_unlock_irqrestore();

// wake up listeners

sock_def_readable() {

__wake_up_sync_key() {

_raw_spin_lock_irqsave();

__wake_up_common() {

ep_poll_callback() {

...

_raw_spin_unlock_irqrestore();

}

}

_raw_spin_unlock_irqrestore();

}

...

The softirq handler performs the following steps:

- Call the driver’s poll method (in this case

ixgbe_poll) - Perform some GRO functions to group packets together into a larger work unit

- Call the packet type’s handler function

(

ip_rcv) to walk down the protocol chain - Parse IP headers, perform checksumming then call

ip_rcv_finish - The buffer’s destination function is invoked, in this case

udp_rcv - Since these are multicast packets,

__udp4_lib_mcast_deliveris called - The packet is copied and delivered to each registered UDP socket queue

- In

udp_queue_rcv_skb, buffers are checked and if space remains, the skb is added to the end of the socket’s queue

Monitoring back-pressure

When attempting to increase the throughput of an application, we need to understand where back-pressure is coming from.

At this point in the data receive path, we could have throughput issues for two reasons:

- The

softirqhandling mechanism cannot dequeue packets from the network device fast enough - The application processing the destination socket is not dequeuing packets from the socket buffer fast enough

softirq back-pressure

For the first case, we need to look at softnet stats

(/proc/net/softnet_stat), which are maintained by the network receive

stack.

The softnet stats are defined

here

as the per-cpu struct softnet_data, which contains a few fields of

interest: processed, time_squeeze and dropped.processed is the total number of packets processed, so is a good

indicator of total throughput.time_squeeze is updated if the ksoftirq process cannot process all

packets available in the network device ring-buffer before its cpu-time

is up. The process is limited to 2 jiffies of processing time, or a

certain amount of ‘work’.

There are a couple of sysctls that control these parameters:

net.core.netdev_budget- the total amount of processing to be done in one invocation of net_rx_actionnet.core.dev_weight- an indicator to the network driver of how much work to do per invocation of its napi poll method

The ksoftirq daemon will continue to call

napi_poll

until either the time has run out, or the amount of work reported as

completed by the driver exceeds the value of net.core.netdev_budget.

This behaviour will be driver-specific; in the Intel 10Gb driver,

completed work will always be reported as

net.core.dev_weight

if there are still packets to be processed at the end of a poll

invocation.

Given some example numbers, we can determine how many times the

napi_poll function will be called for a softIRQ event:

net.core.netdev_budget = 300

net.core.dev_weight = 64

poll_count = (300 / 64) + 1 => 5

If there are still packets to be processed in the network device

ring-buffer, then the time_squeeze counter will be incremented for the

given CPU.

The dropped counter is only used when the ksoftirq process is

attemping to add a packet to the backlog queue of another CPU. This can

happen if Receive Packet

Steering

is enabled, but since we are only looking at UDP multicast without RPS,

I won’t go into the detail.

So if our kernel helper thread is unable to move packets from the

network device receive queue to the socket’s receive buffer fast enough,

we can expect the time_squeeze column in /proc/net/softnet_stat to

increase over time.

In order to interpret the file, it is worth looking at the

implementation.

Each row represents a CPU-local instance of the softnet_stat struct

(starting with CPU0 at the top), and the third column is the

time_squeeze entry.

The only tunable that we have at our disposal is the netdev_budget

value. Increasing this will allow the ksoftirq process to do more

work. The process will still be limited by a total processing time of 2

jiffies though, so there will be an upper ceiling to packet

throughput.

Given the speeds that modern processors are capable of, it is unlikely

that the ksoftirq daemon will be unable to keep up with the flow of

data. In order to give the kernel the best chance to do so, make sure

that there is no contention for CPU resources by assigning network

interrupts to a number of cores, and then using isolcpus to make sure

that no other processes will be running on them. This will give the

ksoftirq daemon the best chance of copying the inbound packets in a

timely manner.

If the ksoftirq daemon is squeezed frequently enough, or is just

unable to get CPU time, then the network device will be forced to drop

packets from the wire. In this case, we can use ethtool to find the

rx_missed_errors count:

ethtool -S <device-name> | grep rx_missed

rx_missed_errors: 0

alternatively, the same data can be found by looking at the following file:

/sys/class/net/<device-name>/statistics/rx_missed_errors

For a full description of each of the statistics reported by ethtool,

refer to this

document.

Application back-pressure

It is far more likely that our user programs will be the bottleneck here, and in order to determine whether that is the case, we need to look at the next stage in the message receipt path. A continuation of this post will explore that area in more detail.

Summary

For UDP-multicast traffic, we have seen in detail the code paths involved in moving an inbound network packet from a network device to a socket’s input buffer. This stage can be broadly summarised as follows:

- On packet receipt, the network device fires a hardware interrupt to the configured CPU

- The hardware interrupt handler schedules a

softIRQon the same CPU - The

softIRQhandler thread (ksoftirqd) will disable receive interrupts and poll the card for received data - Data will be copied from the network device’s receive buffer into the destination socket’s input buffer

- After a certain amount of work has been done, or no inbound packets

remain, the

ksoftirqdaemon will re-enable receive interrupts and return

In order to optimise for throughput, there are a couple of things to try tuning:

- Increase the amount of work that the

ksoftirqdaemon is allowed to do (net.core.netdev_budget) - Make sure that the

ksoftirqdaemon is not contending for CPU resource or being descheduled due to other hardware interrupts - Increase the size of the network device’s ring-buffer

(

ethtool -g <device-name>)

As with all performance-related experiments, never attempt to tune the system without being able to measure the impact of any changes in isolation.

First, make sure that you know what the problem is (i.e.

rx_missed_errors or time_squeeze is increasing), the add the

relevant monitoring. For this particular case, we would want to be able

to correlate the application experiencing message loss with a change in

the relevant counters, so recording and charting the numbers would be a

good start.

Once this has been done, changes can be made to system configuration to see if an improvement can be made.

Lastly, any changes to the tuning parameters that I’ve mentioned MUST be configured via automation. We have sadly lost a fair amount of time to manual changes being made on machines that have not persisted across reboots.

It is all too easy (and I speak as a repeat offender) to make adjustments, find the optimal configuration, and then move on to something else. Do yourself and your colleagues a favour and automate configuration management!